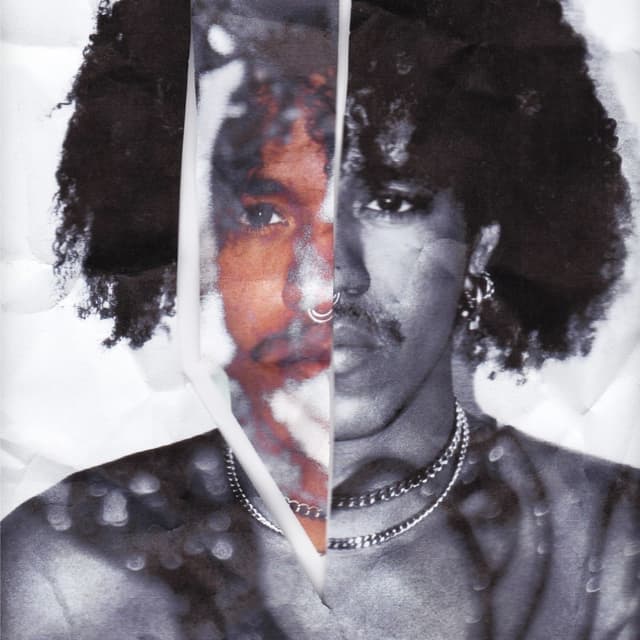

Ocean Evers-Peete is a multi-faceted artist based in Tokyo. From illustration and experimental tech to music projects like DOT.KAI, Ocean explores the intersections of art, sound, and technology. In this interview, he reflects on his journey from North Carolina to nearly a decade in Japan, the joys and struggles of making art in an AI-saturated world, and how Tokyo gave him the freedom to fully explore his identity. Ocean shares his approach to creativity, the importance of community, and why learning to prioritize relationships over recognition has shaped his path.

Self-Introduction

Tell us about yourself. Who you are, where you're from, what you do. And anything about you.

I am Ocean Evers-Peete. And I like to think of myself nowadays, maybe, as a creative technologist. It’s hard to put a solid label on it because, one, I don’t feel like I’m really that good at any one thing, and two, I want to be good at a lot of things. I'm from America. My background is in North Carolina, and New York for my childhood. And then, yeah, I moved to Japan at the dawn of my young adulthood and never looked back. I've been in Japan for almost a decade. The things I do kind of range from just traditional illustration, art stuff, mixed media—to tech and trying to create interesting user interfaces, and fun applications. Messing around with interaction technology like WebGL, and 3D stuff more recently. And a little bit of AI.

You also do music right?

Yeah. I’ve had a healthy interest in music since I was a teenager. I play one instrument poorly, and I’ve made a few projects that were primarily music-focused. The biggest one was probably the DOT.KAI project, which is an alias for myself. The first part of that I did with a group named Dosing in Japan. We had a couple of spin-off projects, some trap metal, some more alternative. Then the second half of that—which is my preferred half, because it's a little closer to my heart—the work I did with Arran Sym, who was also an expat living in Tokyo. We made a full album and a bunch of singles together, and I think we're going to keep working on that as well and see where we go with it. My goal is to mix all these different interests together while also getting better at the individual disciplines: better at instrumentation, production, stage presence. Better at creating unique, singular experiences that bring tech into it—not just 3D and XR/AR, but also microelectronics. Really, I just want to make stuff. Make cool stuff.

How It Started

What inspired you to start working in creative industries?

I don’t think I had a choice. And I think this goes for a lot of my close creative friends too. If you weren’t doing this, you’d go crazy. I can’t imagine just being at an office doing some bullshit. But if I really dig into it: I’m the oldest sibling out of all my brothers, but I had a godbrother who was about seven years older than me. At a really young age, he introduced me to art, anime, video games and all this really cool creative stuff. So I think being exposed to that at a time when a lot of our parents still thought it wasn’t good for kids to be around—but having that direct influence and being there as he was going through the beginning of his artistic process—fed into me and was nurtured as I continued to grow. And the moment I had agency as a later teenager, I started really trying to reach out into other forms that weren't just illustration. My grandfather was another big one. He's one of the first black computer scientists in the Midwest, and he introduced me to technology very early. So I started thinking about, “how does that mix in?” Then from there, it was just meeting a lot of cool people along the way, and that kept teaching me new things.

That's so interesting. Most people start off doing creative stuff as a hobby. For you, how did it turn from a hobby into a professional career?

“Professional” just means you’re doing it seriously. For me, it doesn’t necessarily mean making a bunch of money, or even making money at all. As long as you’re taking it seriously and operating with that mindset, that’s professional. Of course, making money helps, but I’d say the point where I started to consider what I was doing “professional” was when, even while I was in school or working a job, the majority of my time was going into the creative process. I feel like there was a kind of flip. It wasn’t binary, it was more of a sliding scale. But moving to Japan is really when it tipped over. That’s when I stopped thinking of myself as a student who makes music on the side, or an engineer who makes music on the side. I was just… this. And the other stuff was secondary. I also have to give credit to Dosing for helping with that. Coming into Japan on my own, I found a lot of creative spaces and people, which is how I met them in the first place. They already had a strong community that was organized and taking things seriously. Being around that brought me up to speed quickly and gave me access to more resources than I would have had on my own.

Joy and Struggle in Making

For you, there's many different forms of creative stuff that you work on, but what are the moments that make you the happiest?

I think one of the top ones is when something’s done. You listen to it and you’re like, oh, fuck, I made that, that’s crazy. Or you look at it, or you send it to a friend. Actually, let me separate that. Sending something you’ve made to a friend—whether it’s a website that does something unique, a song, or some art—and hearing them say, “Yo, this is sick,” and seeing it make them happy. I feel like I get more joy from making them happy than from finishing it myself. Because honestly, finishing something can be frustrating too. And maybe the third one is when you’re really into it. I don’t even want to call it a “flow state,” but I’ll give an example. I was playing guitar, jamming with my partner and her friend the other day. I don’t think I’m very good, but then I hit a moment where I was doing something, tweaking it, and everyone kind of locked in. We kept it going for ten minutes. At the start, I was thinking, “I’m trash, I don’t know what I’m doing,” but at the end we were all like, “Yeah, that was sick.” It’s that feeling of realizing you’re capable of more than you thought, just because you tried. And I think that’s something that constantly happens in creative spaces. You’re always trying to push past an unknown, or push into a new realm, even if it’s just for yourself and not for the field as a whole. And that’s a sick feeling.

Definitely yeah. Okay, now on the flip side, what has been the hardest experience? Or have you had a time where you thought, I want to quit?

Yeah. I think I went through one of those recently, and it affected all the fields I’m interested in—music, technology, classical visual art. Sometimes the mountain looks very large that you have to climb. And I think most creatives, most artists, are used to climbing that mountain and learning how to scale it down into something digestible, so we can keep making progress without being too hard on ourselves. That balance is always tricky. But sometimes the world changes really fast. The way we create, the way we do art. It depends on building some kind of toolset and routine, something recurring. And that doesn’t always mesh well with sudden, big change. Change can be exciting, but it depends on the type. For me, the advent of AI technology really hit. It touched every field I’m creative in. It changed how people release music, and how artists are viewed online. Not only are you competing with fully democratized streaming platforms, where hundreds of thousands of songs come out every day, but now you also have fake robot people putting out stuff. It’s a lot of noise. And it’s the same with technology. It used to be more of an esoteric skill. I’ll admit, I’m a fan of a little bit of gatekeeping—a tiny bit, not a lot. I liked that you had to work hard to get good at the computer stuff in order to do creative work with it. When you take that away… I think overall it’s not bad. Again, it’s a kind of democratization of creativity. But it also opens the door to a lot of noise, and it devalues some of the hard skills I had built to function. That was anxiety-inducing. In the long run, I don’t think it spells doom. If you’re good at being creative and technical, those skills will always be valuable. But it does create a lot of noise. And when there’s too much noise, that mountain suddenly feels too big. The scale feels overwhelming, and the pressure can be suffocating.

Defining Values

What does being creative mean to you?

I will say, I think that one part of creativity is problem-solving. There’s a technical aspect to some creative processes, and that links directly with the broader, more open-minded, flow-state kind of creativity. For me, being creative is multimodal. It’s about expressing yourself and finding new ways to interpret and present ideas. And that often happens through problem-solving, through some level of technical ability. Because we can all have ideas. The most creative but least technical thing is just thinking, right? You can think of an idea, you can talk about it. Even talking, to some extent, is a technical skill. But the more technical skill and problem-solving ability you have, the more you can deal with that free-flowing mode of thought—those ideas, those opinions, those controversial takes—and actually manifest them. It’s almost like an alchemy. You can transmute them into something physical in the world. I know that’s not everybody’s take on creativity, but for me it’s this balance between free-flowing thought—the mind, the ideas—and the technical hand that can transform those into a specific experience. Whether that’s in music, art, a poem, a video game—anything like that.

How has being a creative impacted your life?

If you ask my mom, probably not in the best way. It’s definitely put me on paths that weren’t straightforward, and because of that, there have been trials—emotionally and maybe even physically—that were tough. It’s not always the easy way to live. But what you get in return is variety, vibrance, and a lot of meaning in different experiences, even outside the creative ones. You get a non-ubiquity to how you experience being alive and conscious. So overall, I would never pick a different way. Maybe I’d refine the route, but I would never choose not to be a creative. I have family and siblings who took more traditional paths. I’m sure there’s creativity in their lives, but it’s often very financially or career focused. I see the benefits they get—stability, consistency, recognizability—but I don’t think I could be happy with that. Even with the negatives and hard parts, it has mostly made my life richer. The highs are higher, even if the lows are lower. On a more direct note, it’s taken me to many countries, introduced me to countless people, and exposed me to new ways of thinking, technologies, and art. All of that has made my life richer, and it will probably continue to do so.

Reflections on Japan / Tokyo

What does Tokyo mean to you?

For me, Tokyo was a place that felt completely polarized compared to where I came from. It embodied permission—the permission to be myself, to fail in any way I wanted, and then to get back up and try something else. I remember when I first came here, I went through so many different fashion changes, shifts in musical taste, new activities, hobbies, friend groups—all of it. I don’t think I would have had access to that much diversity anywhere else. On one hand, Tokyo is almost like a mecca for creativity. On the other, it gave me the freedom to fully be who I wanted to be, without society or government institutions putting limits on me. Culturally, Tokyo and Japan also offered something more fundamental. It’s a very safe place, and in its own way, open-minded—especially about exploring things deeply and artisanally. That’s not something you’re afforded everywhere. As a young Black person at the time I was growing up, I didn’t always feel that freedom. I’m glad to see that globally things have loosened up—you see less stigma now around Black kids doing things alternatively, not following stereotypes. But back then, it was still on the cusp of that. So coming to Tokyo was like: you have access to tools, you have access to inspiration, and you have the freedom to try whatever you want to try.

So that's quite common that people feel when they come to Tokyo. But what is it about Tokyo that gives that feeling? Because on paper, it probably shouldn't be, right?

Yeah, it probably shouldn’t. On paper, you do have a homogeneous society, a kind of monoculture. But I think people just mind their own business. That’s a big part of it. Part of the monoculture is that it’s culturally appropriate to let people be. You don’t interfere. If someone’s acting a fool—you might come together to guide them if necessary—but generally, if you’re not hurting anyone, people just leave you alone.

Is your current life in Tokyo different from what you imagined before coming to Tokyo?

Yeah, definitely. When I first came to Tokyo, despite all the talk about creativity, I was a full-time engineer at Rakuten. I took that job with the express intention of coming to Tokyo to do creative work. This is when that flip happens—are you an engineer who creates on the side, or a creative who works as an engineer just to survive? In my head, maybe just from lack of knowledge and experience, so much of the life I’ve lived has been completely new to me. I thought it would be more streamlined. There have been a lot more diversions, but I’m not mad about them. Usually something good comes out of it, you learn something interesting, or you create something different. At some point, I probably assumed I wouldn’t stay this long. I thought I’d be there for maybe five years or so.

The Road Ahead

What do you want to achieve in the future? And what is your furthest possible self?

That’s a good question. At one point, I was very focused on financial and mainstream success, primarily through music. I’ve met people, become friends, and tasted a bit of success, and that made me realize it probably doesn’t make you as fulfilled or happy as it’s advertised to. For me now, it’s more like a Maslow’s hierarchy of needs approach. Of course, I want to be financially stable. I want to have family or community around me that I can interact with, help, and be helped by, and where we’re all happy doing that. Living in a co-op or just having a house—that’s the base level. On top of that, I want to keep learning and growing, always getting better and exploring new things. I want to push boundaries and create. When I make art, I don’t want to just replicate what someone else is doing. I want to make something new, remix it, or try something completely off the wall. I don’t really focus on financial success. What matters is being in a position where I can learn, innovate, and do it with the people around me, while we’re all safe and taken care of. That’s perfect for me. Commercial success might naturally come with that, but it’s secondary.

When you’re working towards a big goal, what steps do you take to achieve it? Do you take one step at a time, or what’s your approach?

Oh, God. It might be better to ask the people I’ve worked with. I don’t know… I feel like I’m a step person. I think I’m a step person. I like to lay out a roadmap because I get overwhelmed really easily. I have to break things into small, achievable parts, gamify it a little—move through level one, then level two, then level three.

Definitely. I think that’s the best way to achieve goals anyway.

Yeah. There’s even a bit of science behind it—it tends to work really well. Some people are different. They can take on a huge, massive project, throw themselves into it, and get it done. But for me, if I try that approach, I often lose track of what I’m doing and end up moving on to something else. So breaking things down, step by step, into small achievable actions, works best. Then I check against the bigger picture—what does it achieve in the long run? What do you want to achieve? Are you learning? Are you pushing boundaries?

When taking on new challenges or risks. How do you make decisions?

This is where a bit more of my technical brain comes in. I try to approach it like a product manager would, using a chart—though I don’t stick strictly to it. I’m forgetting the name… the Eisenhower matrix. I don’t whip out the chart every time, but I’ve adopted a similar mindset. For example, if we want to do a new album and we’re breaking down the steps, I prioritize. What’s easiest to get momentum rolling? Do those first. What’s necessary? What’s nice-to-have and can be deferred or assigned to someone else? It’s part of breaking things down into digestible steps. When you do that, you can tackle anything. There’s a saying: how do you move a mountain? One pebble at a time. Move them all eventually.

Thoughts to Carry Forward

What would you tell your past self?

Strong zeros are the devil. The club will be open next week. Techwear isn’t that cool, relax. Probably the biggest thing: friendship and family are more important than success. Always prioritize relationships.

Would you not count having. Healthy, stable relationships with families, friends as success?

That’s a form of success. Let me clarify: friendships and family are more important than recognition or notoriety. Lastly, it’s okay to be bad at things and not get them at first. Learn to sit down and focus. When something feels uncomfortable or hard, you’re on the right track.

How do you maintain motivation?

I think I have to. It’s not really a choice. It’s not like, “Do this and that keeps me motivated.” If I don’t, I’ll slip into a really dark depression. If I’ve got a project this week or this month, I have to be motivated. What helps is constantly looking at new things. Living in a place with inspiration, getting outside, talking to people, trying weird stuff you haven’t done before, even stuff that seems stupid. You also have to sit down without a podcast or YouTube for at least 15 minutes a day, so your brain starts spinning in its default mode network. That’s when weird ideas pop up. Like, “What if I built a little sensor that tracked every time I sneezed and then my web app automatically remixed a playlist and sent it to all my subscribers?” Crazy stuff like that. If you let your brain be quiet, bored, and uncomfortable for a few minutes, it starts spitting out ideas. That helps because you need something in the tank when motivation isn’t automatic. If the tank’s empty, you can’t pull anything for the week. You have to have something ready to work with.

Finally, do you have any advice for young creatives starting out?

Yeah. Keep an eye on what’s happening in the world around you, but don’t let it dictate the direction you want to go in. Do what feels interesting to you. For example, take AI. Everyone’s saying it’s going to replace engineers. But if you want to do creative tech or music, who cares if AI can do that now? Do it because you want to do it. And if ten years from now music somehow gets banned… keep making it. (Not legal advice. If that happens and you get arrested, it’s not my fault.) The main thing is to do what you enjoy, because you like it, not because of what the world thinks or what other people say you should be doing.

Follow and connect with Ocean below...